“This ongoing social effort to correct errors our subjectivity leads us into is what I call objectification – Brookes”

Is everything information?

Is an ox grazing in the field information?

It is in part – almost.

It might or might not be part of the process.

An ox grazing in the field is the “real world” without representation.

If all humans die, there will only be the feeling and instinct of animals, as words will have disappeared.

- The cougar will smell the ox.

- The ox will moo to the cow.

The world without humans will have no representation and, therefore, will be timeless.

The ox will only exist in that second grazing in the field.

Only the human being is capable of recasting the ox in time.

The grazing ox is a quasi-reality with no filters. It will be filtered by whoever is watching it, whoever looks at the scene with a certain point of view – the ox grazing in the field –.according to older or younger eyes, more rural or less rural eyes, etc.

The ox in the pasture is the world in almost a pure state. When it is represented, it’s filtered by our interests/lack of interest with more or less efficacy.

For those going by, the ox grazing in the pasture is a landscape.

What if someone wants to represent it?

“Papa, look at the ox in the pasture.”

This presupposes language.

And the desire to highlight it in the present time.

Or else, to preserve it.

The ox will only exist outside that time – in which we relate to it, alive, in the pasture – if we store it in our memory and tell someone else.

“Auntie, I saw an ox grazing in the field.”

Or document it, through some kind of record, text, photo, video, drawing, sculpture, etc.

Thus, in the relation human being-ox in the pasture, we have the real being revealed in a process that we might call informational, going through the contact with the fact in process, the interest in recording it, and preserving it in time.

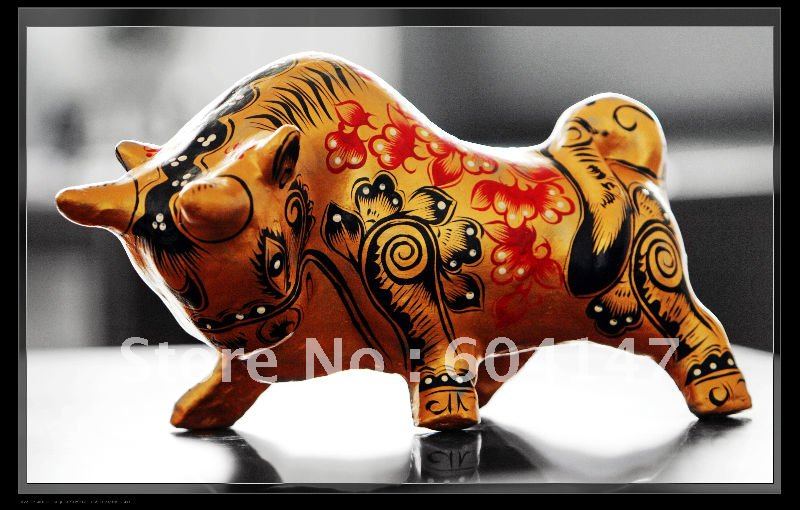

When we observe the ox in the pasture outside our memory, we create a document. If we want to pay homage to it with a statue, we erect a monument.

The difference is that I can carry the document from one place to the other.

While the monument, depending on its size, stays in its site, static, almost an ox, although more durable, making it into a perennial ox in the pasture.

Until someone decides to destroy it.

(Or someone decides that a grazing-ox statue is not adequate for a square and should be replaced by the statue of a relative – a typical decision in Brazil).

The ox grazing in the field is a process that may generate a document.

Information is the whole process of watching the ox, recording it, disseminating it, as well as the interpretative assimilation of whoever sees the document about the ox in the pasture and creates a new representation, or even a new document.

A poem about the photograph of the ox in the pasture.

Or a description of that photograph or poem to be retrieved, something called documentary language in archival science. This is the effort of achieving maximum representation with minimum words for those avid for information.

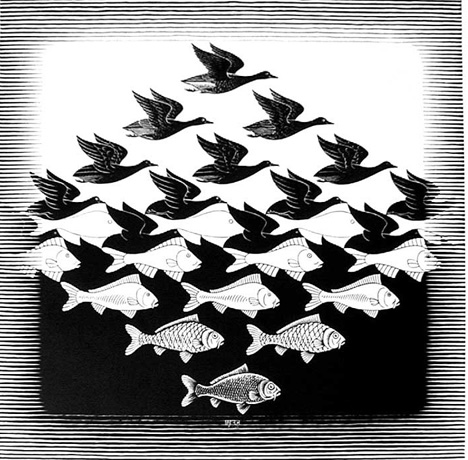

Thus, the document is the partial register of the real by whoever made the record.

It’s never the real, but part of it, filtered by someone.

We need information to transform what is complex into simple, thus enabling our limited minds (despite all their potential) to apprehend and make decisions.

And the ox, who’s got nothing to do with all this, is the ox who one day grazed in that field, or in any other field, depending on the record.

Information is a process that tends to unfold into documents.

Thus, the world is always a representation of itself or of our memory, either transitory or documented.

The first documents, if we could call them as such, were virtual documents, stored in human memory and transmitted orally from parents to children – stories, poems, repeated theatrical plays – since language was invented about 100,000 years ago, so we could:

- Name things through nouns

- Put them in movement through verbs

- And express our subjectivities through adjectives

In fact, every information process is a simplification of something more complex that we will never be able to represent. Complexity forced us to invent writing some 5,000 years ago to record things.

Memory was too fleeting and inaccurate.

This doesn’t mean documents don’t have these characteristics, but less so.

Thus, representing the world is an eternal incompleteness that at best expresses a determined fact in movement, a process.

Information will always be an illusion of the unreachable real.

A version of the facts.

Hence, the more facts we place in a version, the closer we will be of what was meant to be represented – without ever reaching the actual fact.

The closer we will be to the process in itself, but never of the pure process. Just the closest we can get to it, now with increasingly sophisticated resources to represent it.

No matter what we want, to be informed is to be more or less deluded.

However, there are moving forces at work in the information process.

- On one side, volume.

The greater the volume, the more complex to find what we want and the more sophisticated the representation, through methodologies, technologies, and specialized professionals.

- On the other side, time.

Information, as a process in movement, needs to be available at the right time and has to be found before the decision is made. There is no point in knowing the schedule of a train that has already departed.

- At a reasonable cost.

It’s no good to have top-rate information that nobody can afford and that remains inaccessible to increasing numbers of people.

Thus, information is an attempt to create a dynamic balance between volume, time, and cost.

To inform is to try to inject the maximum number of facts into versions to help reduce the illusion of the represented process. Disinformation and manipulation are just the opposite.

What do you say?

This text was inspired by this one.

Twitter in English. Follow me.

Twitter in Portuguese. Follow me.

Translated by Jones de Freitas. Edited by Phil Stuart Cournoyer.